© WTA Publishing

METEOR

From the preface, by the author

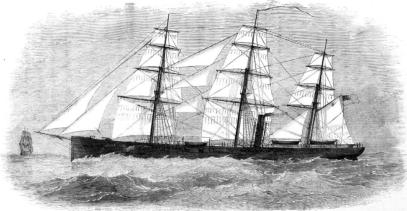

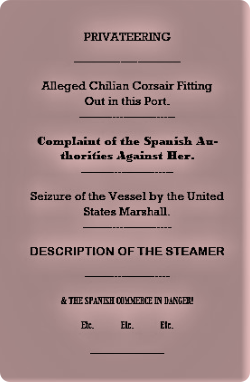

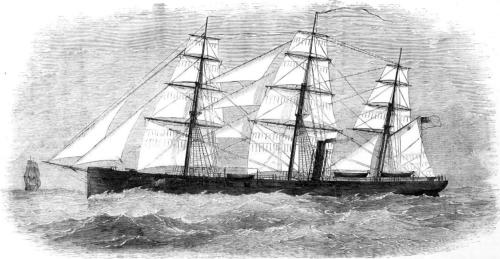

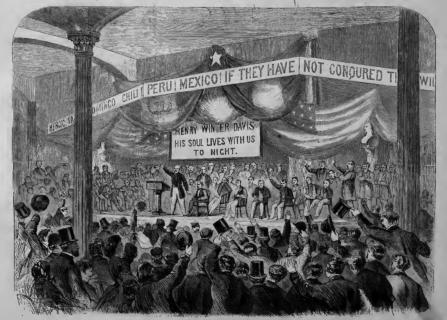

“I wrote a book (The Bombardment of Paradise) about the 1865-66 war between Spain and Chile and, in particular, the bombardment of Santiago’s old port city of Valparaiso. I came across an odd but alluring story of an “ajente confidencial” who went to New York to press the U.S. government into supporting the Chilean cause and, more discreetly, to seek out and buy warships and arms with which the blockading Spanish navy might be subdued if not sent to the bottom of the Bay of Valparaiso. The confidential agent was Benjamin Vicuña Mackenna. He ended up in the New York courts – twice – for his troubles. One of those troubles was an attempt to buy a vessel, built for the Civil War, called Meteor, at the time the fastest sailing ship afloat. “It is not possible to research and write about the history of Chile without coming across Benjamin Vicuña Mackenna. It really does not matter if you are concerned with pre- colonial history, the war of independence, irrigation in the Atacama Desert, silver mining, corruption in high places, nineteenth century inventions of agricultural machinery, or some of the nation’s most infamous criminals, because this formidable author wrote about them all and much more. He recorded history copiously, but he also experienced it from close-quarters and often made it. “Vicuña Mackenna managed to find a role in Peru during one of its violent political upheavals, in Mexico during the country’s occupation by France and in so many places where activists from across the South American continent were seeking an American response to new aggressions by the European powers that had dominated them for much of the previous four centuries. He was a Chilean patriot with a large sense of patriotism. “He travelled widely, twice as an exile. He knew Europe and the United States better than most of their citizens; he was immersed in their histories and their cultures. He watched the horrors of the Franco-Prussian War from up close and was in Paris in the aftermath of the Commune. He recorded everything and reported as a foreign correspondent for newspapers in Chile. “The Meteor story is recounted in Part Two of this book. Yet as I researched and wrote I became aware that I could not restrict myself to those 10 months of Vicuña Mackenna’s lifetime. It was obvious that whatever the failures and naiveties of his efforts in New York, I was dealing with an extraordinary personality. He was a great man. And he would have been a great man in no matter what country in that epoch. “Early on he was a revolutionary; perhaps it is better to call him a liberal-romantic in the European mould, especially that of France. He fought the anti- Conservative causes of the 1850s. Later he secured help for war widows and their children, insisting on the debt society owed to its military. He changed the education system: evening classes for workers, wider primary and secondary schooling and university reform, particularly to separate the state system from the church. As Intendente, he transformed Santiago. He pursued prison reform, based on observations during his travels in the United States and Europe, and re-organized the police. He pressed causes and institutions that recognized women’s rights and he established the first society for animal protection. Late in life he became a proud officer of Santiago’s new fire service, having campaigned long and hard for such a vital service in the capital. “Certainly, he did not win every campaign he fought. Some of his ideas would be anathema in today’s Chile, notably his determination to “civilize” the Mapuche lands of Araucania. But he triumphed frequently, and to those causes he fought in vain he still brought a lively conviction and commitment that even his opponents had no option but to admire. One of his famous biographers, Luis Galdames, wrote: “On 25 August 1861, Vicuña Mackenna reached his 30 years; but he had worked and acted with such intensity that, without hyperbole, one could say he had already completed his life.” Another celebrated historian, Francisco Encina, stated: “The history of Chile does not contain anyone of a comparable dynamism. What he achieved during the 55 years of his life could barely be achieved by ten normal men.” “So, ‘Meteor’ is something of a metaphor for a life that rocketed into the stratosphere early, blazed ardently and fell to earth prematurely. It is certainly a life that deserves recognition outside as well as inside Chile. Benjamin Vicuña Mackenna was not an ordinary man.”

© WTA Publishing

METEOR

From the preface, by the author

“I wrote a book (The Bombardment of Paradise) about the 1865-66 war between Spain and Chile and, in particular, the bombardment of Santiago’s old port city of Valparaiso. I came across an odd but alluring story of an “ajente confidencial” who went to New York to press the U.S. government into supporting the Chilean cause and, more discreetly, to seek out and buy warships and arms with which the blockading Spanish navy might be subdued if not sent to the bottom of the Bay of Valparaiso. The confidential agent was Benjamin Vicuña Mackenna. He ended up in the New York courts – twice – for his troubles. One of those troubles was an attempt to buy a vessel, built for the Civil War, called Meteor, at the time the fastest sailing ship afloat. “It is not possible to research and write about the history of Chile without coming across Benjamin Vicuña Mackenna. It really does not matter if you are concerned with pre-colonial history, the war of independence, irrigation in the Atacama Desert, silver mining, corruption in high places, nineteenth century inventions of agricultural machinery, or some of the nation’s most infamous criminals, because this formidable author wrote about them all and much more. He recorded history copiously, but he also experienced it from close-quarters and often made it. “Vicuña Mackenna managed to find a role in Peru during one of its violent political upheavals, in Mexico during the country’s occupation by France and in so many places where activists from across the South American continent were seeking an American response to new aggressions by the European powers that had dominated them for much of the previous four centuries. He was a Chilean patriot with a large sense of patriotism. “He travelled widely, twice as an exile. He knew Europe and the United States better than most of their citizens; he was immersed in their histories and their cultures. He watched the horrors of the Franco- Prussian War from up close and was in Paris in the aftermath of the Commune. He recorded everything and reported as a foreign correspondent for newspapers in Chile. “The Meteor story is recounted in Part Two of this book. Yet as I researched and wrote I became aware that I could not restrict myself to those 10 months of Vicuña Mackenna’s lifetime. It was obvious that whatever the failures and naiveties of his efforts in New York, I was dealing with an extraordinary personality. He was a great man. And he would have been a great man in no matter what country in that epoch. “Early on he was a revolutionary; perhaps it is better to call him a liberal-romantic in the European mould, especially that of France. He fought the anti- Conservative causes of the 1850s. Later he secured help for war widows and their children, insisting on the debt society owed to its military. He changed the education system: evening classes for workers, wider primary and secondary schooling and university reform, particularly to separate the state system from the church. As Intendente, he transformed Santiago. He pursued prison reform, based on observations during his travels in the United States and Europe, and re-organized the police. He pressed causes and institutions that recognized women’s rights and he established the first society for animal protection. Late in life he became a proud officer of Santiago’s new fire service, having campaigned long and hard for such a vital service in the capital. “Certainly, he did not win every campaign he fought. Some of his ideas would be anathema in today’s Chile, notably his determination to “civilize” the Mapuche lands of Araucania. But he triumphed frequently, and to those causes he fought in vain he still brought a lively conviction and commitment that even his opponents had no option but to admire. One of his famous biographers, Luis Galdames, wrote: “On 25 August 1861, Vicuña Mackenna reached his 30 years; but he had worked and acted with such intensity that, without hyperbole, one could say he had already completed his life.” Another celebrated historian, Francisco Encina, stated: “The history of Chile does not contain anyone of a comparable dynamism. What he achieved during the 55 years of his life could barely be achieved by ten normal men.” “So, ‘Meteor’ is something of a metaphor for a life that rocketed into the stratosphere early, blazed ardently and fell to earth prematurely. It is certainly a life that deserves recognition outside as well as inside Chile. Benjamin Vicuña Mackenna was not an ordinary man.”